Published: Sep 16, 2021 by Gavin

A few weeks ago, British Columbia announced that they were implementing a vaccine passport system. It started being enforced this week and to prepare for that they have a system to download the “cards” from the government’s Health Gateway website. Turns out, the card is a QR code that you can download to your phone and present to businesses. They’ve released a companion app that businesses can use to scan the QR codes and verify they are valid proofs of vaccine. I was curious how the system works, so I did some reading and wrote some code to see what I could learn.

My BC vaccine card (spoiler alert, I'm confident enough that the cards don't leak private information that I'm comfortable sharing my real vaccine card here)

The vaccine card itself is just a QR code on a green background, with my name and the date I downloaded it presented on top. No real personal information is being leaked by looking at the card, the BC government suggests also confirming photo ID with verification of the vaccine card, so there’s much more data someone will see looking at my license. I’ve seen a lot of people questioning what the verification app does and worrying that any random restaurant employee would have access to their personal data. I scanned my own card to see what the interface looks like and here it is:

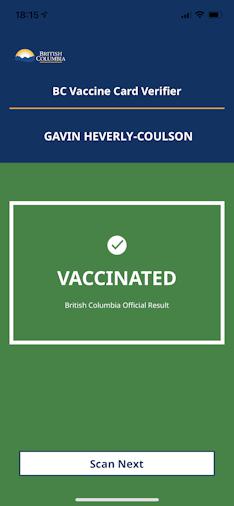

Screenshot from the BC vaccine verification app

So that’s it, a happy green background, a check mark saying the card is verified, and my full name. Doesn’t look like the system is leaking any personal data here, that’s great. Let’s take this a step further and assume the person scanning my card isn’t actually scanning it, but taking their own picture of it to decode later for nefarious purposes.

What’s in the card?

Disclaimer: I am not an expert in these vaccine cards or the technologies used to implement them. What I describe below is my own understanding of the technologies from reading and experimenting, anything I say may be incorrect. All the code I used to generate this data is in this Github repo.

The first thing to do is decode the QR code.

Fortunately for me, plenty of tools exist to do that automatically.

It might be fun some day to write my own QR decoder to understand how they work, but that’s not the goal for today.

I chose to use the QRCodeDetector() function in the Python OpenCV library, so I didn’t have to bother with cropping the image.

I can present it with the same screenshot I’ll be showing businesses and it will find the QR code in the image and decode it for me.

When we do that, we get something that looks like: shc:/5676295953265460346029254077280433602870286567675422280928623725376...

This has been truncated for the sake of readability, in actuality we get the shc:/ prefix followed by about 1700 numbers.

That shc:/ prefix tells us that the following data is an encoded version of the SMART Health Card.

This an open standard developed by a group at the Boston Children’s Hospital to provide a secure and private way to share health test results and vaccination status.

They have an extensive technical document describing the spec for the cards and the motivations behind them.

The cards are based on the widely used JSON web signature (more on that later) format.

Clearly, this is a format that has had a thought put into and consideration for how to share this health information in a verifiable, secure, and private way.

Let’s take the next step and see what that long string of numbers actually represents. To do that, we take pairs of numbers, add 45 to them, and then convert the resulting integer into its corresponding ASCII character.

56 + 45 = 101 -> e

76 + 45 = 121 -> y

29 + 45 = 74 -> J

...

Doing this on the full string of numbers we got from the QR code, we get something that looks like a string of gibberish (line breaks added for clarity of reading):

eyJhbGciOiJFUzI1NiIsInppcCI6IkRFRiIsImtpZCI6IlhDcXhkaGhTN1NXbFBxaWhhVVhvdk1fRmpVNjVXZW9CR

kdjX3BwZW50MFEifQ.7FPLbtswEPyVYHvVg5LrWNYtdYM2QOAUjWOgCHygSdpiwYdAUkJdQ__epe2gbuHk1GMFARJ

Xu7OzM6s9SO-hhiaE1td57jV1oRFUhYZRx7O28TRjNO-LHBM74SABs95AXVyPSDUmk6LMSAI9g3oPYdcKqJ8vgSGG

4_4ds73kxRRBXs-RWndG_qRBWvNm4vGQxgOsEmBOcGGCpOqxW38XLERKm0a6pXA-YtXwPiNZgZgx-qEzXCHdPTjhb

eeYWBzow-lDchoHmFUK0Y5ssIHb4YyI3Cn15BQmvNTXBBNeDheAv-BIWB8VpFocQaiWCvHg8-3y9uv9t3T28HT_-D

DHnK3sBXJ-hk83y7s5rAYccS1Rgo80RLRiWl2npErJCIYhucineJvP3Z9C-0BDF3eBWd0qEQTHYE8Zk0bMLD8gMMu

l2R6o-50PQp9WB_1p1CSzbptHbXMvec76HwiAFbFXSSYQWf5d5Y3VgmfSbGzu0bLfBdV4UhC8KnxMYVgNCbQnAQ-j

bIQTJs51rj8mWcY6d_gUhVpIfWxfFikZp2WFHZQN806vcZdrGBFSjkcx2gq3sU7HKE5HWbD4tgcufatotGhJDbNdL

9zVzBr0Jsp2NYsLIdCB1WsmlP9NWJybMEnL-J-cm0DG5awsbv6JCXgPwy8AAAD__wMA.Q55LPKCoQiJm7GqSkea4N

aj87CWD2Rhk-p4f_3nMQZtGrC-pXX_WPwypH72L-npi-yPPVOg7y-tiRgSisUsy

This gibberish is actually URL-safe Base64 encoded data, with one exception. If you look carefully, you will see two periods mixed into all this. These are illegal characters in URL-safe Base64, so what are they doing there? It turns out, they’re delimiters and this string is actually three separate Base64 encoded strings. From the JWS format, we know that these should be the “header”, “payload”, and “signature” respectively. Let’s run them through a Base64 decoder and see what we get.

Header

The header comes out looking like a fairly straightforward JSON object.

{

"alg": "ES256",

"zip": "DEF",

"kid": "XCqxdhhS7SWlPqihaUXovM_FjU65WeoBFGc_ppent0Q"

}

From the JWS spec, I know that this describes how to parse and verify the data in the payload and signature.

The “alg” section tells use which cryptographic algorithm was used to sign the data, which is important for verifying the authenticity of the data.

In this case, ES256 is shorthand for ECDSA with the P-256 curve and SHA-256 hashing.

Unless you want to learn cryptography, exactly what that means is irrelevant here beyond knowing that this is modern cryptographic signature.

Next, the “zip” section tells us DEF, which means that the payload was compressed using the DEFLATE algorithm.

Finally, the “kid” section gives an ID for the public key that was used to sign this data.

We’ll see in a moment how to use that.

Payload

When decoded, the payload’s Base64 just becomes a string of bytes. I won’t show that here because it’s not particularly interesting, but remember that we were told in the header that the payload was compressed with DEFLATE. Inflating it, we get a large JSON object with some interesting data in it. Starting at the top, we see:

{

"iss": "https://smarthealthcard.phsa.ca/v1/issuer",

"nbf": 1630850712.0,

"vc": {

"type": [

"https://smarthealth.cards#covid19",

"https://smarthealth.cards#immunization",

"https://smarthealth.cards#health-card"

],

...

}

This is telling us that we have a SMART Health Card with some links to information about the cards.

The “iss” section is also giving a link, but in this case it is pointing to information about how to verify the data.

According to the SMART Health Card spec, in the “iss” section is a link that when appended with /.well-known/jwks.json will point to the public keys used to sign this card.

Going to that link we get yet another JSON object.

{

"keys": [

{

"kty": "EC",

"kid": "XCqxdhhS7SWlPqihaUXovM_FjU65WeoBFGc_ppent0Q",

"use": "sig",

"alg": "ES256",

"crv": "P-256",

"x": "xscSbZemoTx1qFzFo-j9VSnvAXdv9K-3DchzJvNnwrY",

"y": "jA5uS5bz8R2nxf_TU-0ZmXq6CKWZhAG1Y4icAx8a9CA"

}

]

}

This provides all the information we would need to verify the health card hasn’t been tampered with. Of particular interest right now is the “kid” section, which is identical to the “kid” from the header. This tells us that the keys we just downloaded are in fact the same ones used to sign this health card.

Looking further down the JSON payload is my personal COVID-19 vaccination information. First we have an entry that defines me as the patient:

{

"fullUrl": "resource:0",

"resource": {

"resourceType": "Patient",

"name": [

{

"family": "HEVERLY-COULSON",

"given": ["GAVIN"]

}

],

"birthDate": "1986-08-03"

}

}

This adheres to the SMART Health Card spec that says the only personal information that should be included is full name and birth date. Great, BC isn’t pulling anything funny here.

Then, we have two sections describing my two COVID-19 vaccinations:

{

"fullUrl": "resource:1",

"resource": {

"resourceType": "Immunization",

"status": "completed",

"vaccineCode": {

"coding": [

{

"system": "http://hl7.org/fhir/sid/cvx",

"code": "207"

},

{

"system": "http://snomed.info/sct",

"code": "28571000087109"

}

]

},

"patient": {

"reference": "resource:0"

},

"occurrenceDateTime": "2021-05-28",

"lotNumber": "3002538",

"performer": [

{

"actor": {

"display": "Vancouver Convention Centre"

}

}

]

}

}

It says I received an immunization, on May 28 at the Vancouver Convention Centre, which is all correct.

To know what the immunization was, we need to look at the vaccineCode.

There are two resources provided there, SNOMED and FHIR, which are two international databases of medical procedures and medicines.

The BC government provides a spreadsheet of the SNOMED mappings for all the vaccinations approved for use in the province.

Finding code 28571000087109 in the spreadsheet, we see that it is “COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna messenger ribonucleic acid-1273 100 micrograms per 0.5 milliliter suspension for injection Moderna Therapeutics Inc. (medicinal product)” - the Moderna mRNA COVID-19 vaccine that I received.

Signature

The last piece of the data included in the QR code is the signature. After decoding the Base64 string, we are presented with another string of bytes. I won’t go into details of exactly what is in here (mostly because I don’t actually know), but it is sufficient to know that it is a digital signature created using the the ECDSA algorithm mentioned above. We can verify that the data in the payload wasn’t tampered with using this signature (and that’s exactly what the verification app is doing). If we compute a signature from the payload using the keys retrieved earlier and compare it to this one, we’ll know that this is real and accurate data.

This is a key part of the whole vaccine card system. Without it, I could take someone else’s valid QR code, do all the work described above to decode it, edit their personal details for my own, and then create a new QR code containing my name. But, by doing that, the signatures will not match, telling the system verifying your vaccine card that it is not authentic. This is the essence of cryptographic signatures, you can use the public key (the one we downloaded earlier) to verify a signature, but we cannot generate a new signature. To do that, we would need the corresponding private key, which will be a closely guarded secret held by the BC government and used to create these vaccine cards.

What have we learned?

It looks to me like the vaccine cards are well-thought out technically, so as to not leak any unnecessary personal information, either when scanning it or when cracking it open to see what’s inside. In fact, I’m confident enough in that assessment, that I’ve included a screenshot of my vaccine card at the top of this post. Hopefully this helps someone feel a little more confident that their privacy isn’t being unduly violated when they’re asked to show their vaccine card to have drinks with friends or eat out.

Thank you to this Reddit comment for sending me down this path and providing the initial information I needed to crack open my own QR code.